Note: This article will use People First Language since we do not know the reader’s preference.

The word “disability” may feel uncomfortable to use, let alone teach about, in the art room! What if I don’t say the right thing? What if I don’t know enough information about it? What if it singles students out and makes them uneasy? There can be many “what ifs,” and that’s okay! It’s good to ask questions because it signifies curiosity and can identify an area to grow in. Let’s stretch ourselves and our art curriculums and explore what it can look like to integrate artists with disabilities and why it matters.

What are the benefits of integrating artists with disabilities into your curriculum?

Before diving into this question, let’s establish what a disability is and some other baseline terms. This will allow us to move forward on the same page.

Understanding the principle of windows and mirrors can be helpful when considering the benefits of integrating artists with disabilities. Although this refers to stories, the same can be applied to artwork. After all, artworks are visual stories. People see the outside world through a window. If we use art as a window, we can use it to expose students to history, new perspectives, and experiences. Mirrors let us look at ourselves. Artwork can reflect our students’ complex identities. When it does, it can empower students and “build connection and a sense of belonging.”

Bringing artists with disabilities into lesson plans can be another window of human diversity to expose our students to new perspectives and experiences. This exposure can create deeper connections within an artwork or process. This larger awareness can also develop empathy and make our students more curious learners. It can also widen our own “understandings of human variation and differences.” Artists with disabilities can be a mirror for students who have a disability and remind them they belong in the art room.

Here are nine tips to keep in mind as you include artists with disabilities in your art room and curriculum.

Get in touch with an admissions counselor to learn more about Art and Diverse Learners, Choice-Based Art Education, and Instructional Strategies for Art Teachers. In these graduate courses, you will learn inclusive practices and how you can promote change in your classroom to help all students feel seen and succeed.

1. Add artists organically.

Include artists with disabilities if and when it fits within your existing lesson plans. There is no need to make a big deal out of it or draw special attention to the artist. Introduce them just like you would anyone else.

The tendency can be to admire artists with disabilities, framing it with, “Look what they overcame!” While this can be inspirational, it can also be detrimental. When “individual artists are admired for their ability to create work similar to other able-bodied artists… [it] affirms the perception of people with disabilities as limited in their activities, as well as the notion that artists with disabilities aspire to be like ‘normal’ artists.” Many people with disabilities and artists with disabilities “do not necessarily want to ‘emulate the norm…’ rather, they have full and rewarding lives they could not imagine living any other way.”

2. Display artwork on your walls.

Just like with any other artist, if you like an artist’s work, hang it on your wall! Seeing it on your wall every day may remind you to reference that artist more often. Making work easily accessible will also inspire your students as they make artistic choices daily. It is also a way to reflect broader ideas of what is “normal” and acceptable.

3. Consider the language you use.

Words have power and can shape how we see the world. Remove ableist language to better frame conversations. Ableist language assumes a person with a disability is of lesser value. For specific examples of how to eliminate ableist language, read this article.

4. Include a variety of artists.

Remember, disabilities come in all shapes and sizes. Some may be cognitive, and some may be physical. Some disabilities may be obvious, and some may be hidden. The most common artists with disabilities art teachers share are ones who “… mainly represent North American and European artists who produced work in the last one hundred and fifty years.” Broaden your scope and include artists from multiple time periods and countries. Reference a wide range of artists and disabilities when possible to show students how wonderfully diverse artists and people can be. Students will “… recognize disability for its commonality… rather than its exceptionality.”

5. Mention the disability.

All artists, disability or no disability, use their life and experiences to inform their artwork. Disability is a valuable part of life and experiences. Many students do not have the life experience or insight to make connections on their own. As teachers facilitating learning, we need to explicitly mention an artist’s disability so students can make clear connections.

Many teachers say they share an artist’s disability “when relevant.” This practice is problematic because, as stated above, “process and content are inextricably tied to how we inhabit the world.” It is always relevant! When we withhold this information from our students, it can limit their definition of artistic ideas and objects. It can also limit connections, exposure, and opportunities to grow and learn.

6. Use children’s books.

If you are nervous about discussing disability in front of your students, take a small step by reading a children’s book. This is a low-pressure way to introduce disabilities and what they can look like with fictional characters. This is also a “scripted way” to bring a topic you are unfamiliar with into your classroom.

Take the time to preview books to ensure they represent disability in a positive light and do not reinforce stereotypes. “This includes the representation of people with disabilities as the object of pity, sinister and/or evil, a burden, incapable of fully participating in life, a supercrip, nonsexual, an object of violence, and laughable.”

7. Focus on specific disabilities not represented in your classroom.

In order to cultivate a classroom environment where all of your students feel safe, do not single anyone out. Focus on specific disabilities that are not represented in your classroom. Students with disabilities can still relate and see themselves reflected in the curriculum more anonymously.

8. Build background knowledge.

As mentioned earlier, students often do not have the life experience or insight to make connections on their own. Take the time to build background knowledge, just like you would for any other new topic. Distribute news stories or show movie clips to convey a range of perspectives about a specific disability.

9. Share personal stories.

Encourage students to share and participate in the discussion by forging the way. Go first and model how to share. If you have a personal relationship with a friend or family member who has a particular disability from your lesson, talk about it. It can make the disability more “real” for students. It can also open the door to student questions you may be able to answer.

Now that you have several tips in your repertoire, you may be wondering what artists to showcase. There are many artists with disabilities that are very likely already in your curriculum. According to a survey of Illinois teachers, Chuck Close is one of the most commonly referenced artists with a disability due to his paralyzation, followed by Frida Kahlo, who had polio and lifelong injuries from a bus accident.

Other artists already in your curriculum may include:

Get started with these seven artists with disabilities.

Note: Peruse the links below to determine if they’re appropriate to share with your students.

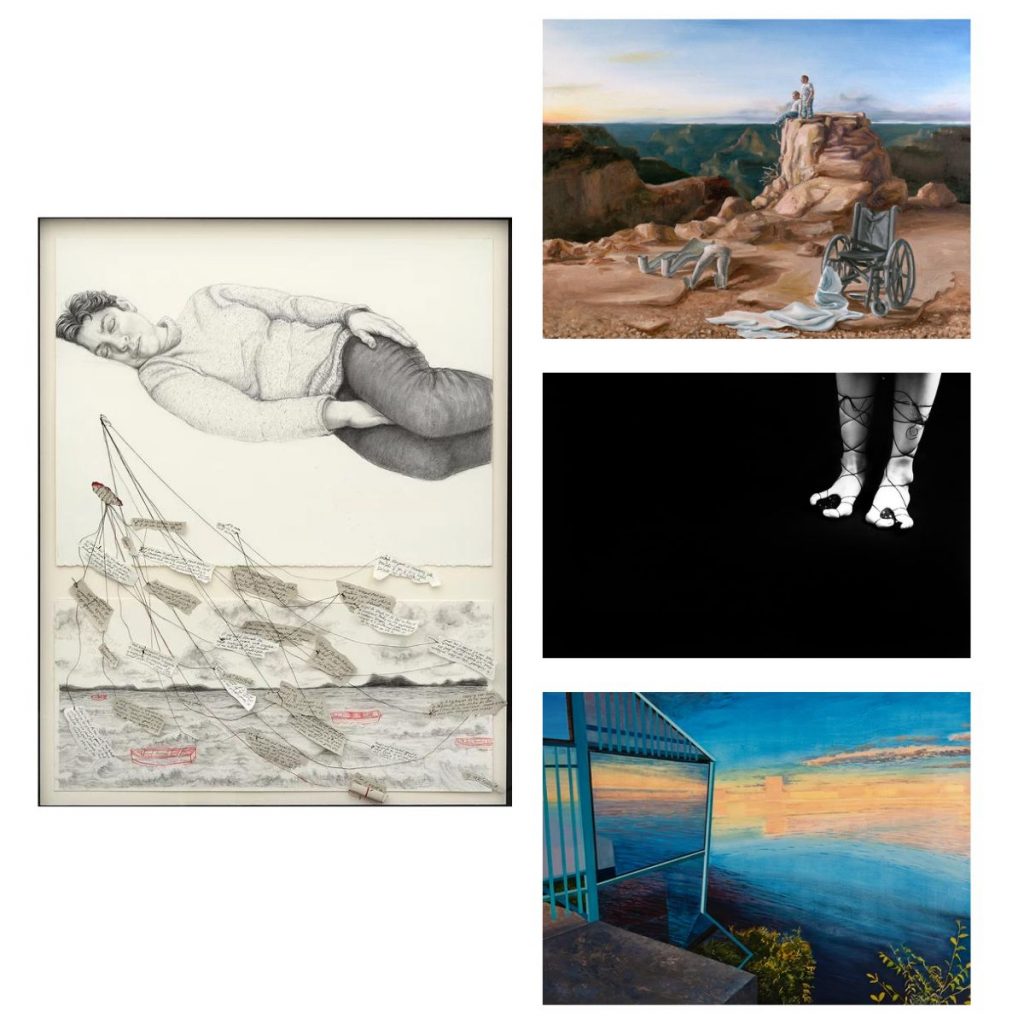

Below is a list of seven artists with disabilities, some of whom make Disability Art. This is a great list to get you started if you want to incorporate artists who are currently practicing and exhibiting.

- John Behnke

Behnke bases his fluorescent acrylic paintings on real places that are altered from his memory or dreams. - Laura Ferguson

Ferguson’s subject matter is her scoliosis and curving spine. She combines drawings with x-rays and scans to merge the worlds of medicine and visual art. - Brooke Lanier

Lanier has retinal detachment, but it doesn’t stop her from painting exquisite waterscapes. - Riva Lehrer

Lehrer’s work is best known for her representations of people with physical disabilities who have been stigmatized. - Sandie Yi

Yi is a sculptor and fiber artist who designs and constructs wearable art for her unique body morphology. - Stephen Wiltshire

Wiltshire is a British architectural artist with autism and is mute. He draws incredibly detailed cityscapes from memory. - John Wos

Wos has a congenital condition that weakens his bones. He depicts his heightened sensitivity to the world around him in his artwork.

Incorporating artists with disabilities is similar to how you would approach exposing your students to any other window of human diversity. It is worth the extra effort and temporary discomfort to ask questions and learn alongside your students. The payoff can be rewarding! Student engagement and curiosity levels can increase, and students will cultivate empathy and build connections. We hope the tips and artists above equip you to become a more reflective art educator and get started with a more inclusive art curriculum!

If you want to explore more, here are resources to find additional artists with disabilities:

Who is your favorite artist with a disability to share with your students?

What tips do you have for integrating artists with disabilities into the curriculum?